The Importance of Blanket Bog Restoration in Ireland

With environmental issues becoming increasingly important, attempts are being made to return Irish bogs to their natural state, with conservation initiatives like the Active Blanket Bog Restoration Project. Preservation efforts such as this are among the most important environmental initiatives, as blanket bogs act as vital storage containers for large amounts of carbon.

The West of Ireland is home to some of the largest intact areas of active blanket bog in all of Europe. Blanket bogs are wild areas formed of peat soils, which formed over thousands of years partly from the decomposed remains of plants. ‘Active’ refers to a blanket bog that is still peat-forming or still growing. Among the last intact active bogs in Europe is Owenduff bog in Co. Mayo, part of the Wild Nephin National Park.

Efforts have been made to make more use of blanket bogs in the past. Forestry was seen as something that would boost the local economy in remote areas where blanket bog cover is extensive, and conifer species such as sitka spruce and lodgepole pine were planted in peatland areas. However in some cases, especially on very wet bogs, these efforts to establish commercial forestry failed as the trees did not grow well.

The bog restoration project is funded by the European Union and the semi-state forestry agency, Coillte. It is one of a number of successful projects and programmes aimed at enhancing biodiversity, in addition to policies designed to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels – such as incentives for solar panels in Ireland. There are 4 sites covering 1,212.3 ha in the bog restoration project consisting of unplanted, partially or wholly afforested blanket bog habitat.

Many project sites are located in north Co. Mayo, where the full range of blanket bog types occur from lowland to mountain blanket bog. Most of the bog here also lies within sensitive river catchments, i.e. where water quality is very high. This means that the protection of watercourses is an important consideration. The Active Blanket Bog Restoration Project aims to achieve the restoration of blanket bog at selected sites owned by Coillte.

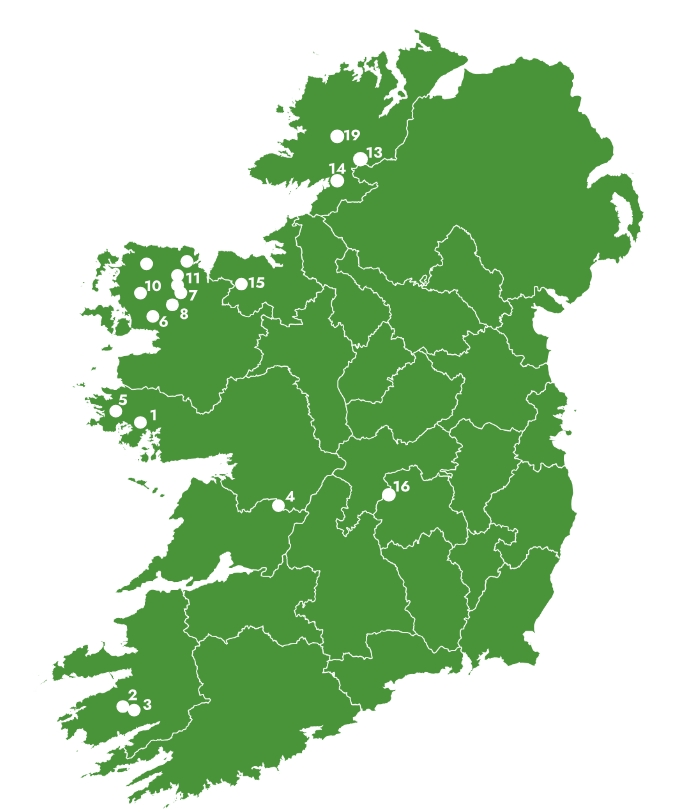

Restoration Locations

- Cappaghoosh, Co. Galway

- Garrane, MacGillycuddy’s Reeks, Co. Kerry

- Dromalonhurt, MacGillycuddy’s Reeks, Co. Kerry

- Pollagoona, Slieve Aughty, Co. Clare

- Emlaghdauroe, The Twelve Bens, Co. Galway

- Bellaveeny, Nephin Beg, Co. Mayo

- Eskeragh, Crossmolina, Co. Mayo

- Eskeragh, Crossmolina, Co. Mayo

- Owenirragh, Glenamoy, Co. Mayo

- Glencullin Lower, Bangor-Erris, Co. Mayo

- Shanvolahan, Crossmolina, Co. Mayo

- Shanvolahan, Crossmolina, Co. Mayo

- Croaghonagh North, Barnesmore Gap, Co. Donegal

- Carrick Barr, Lough Golagh, Co. Donegal

- Sessuegilroy, Ox Mountains, Co. Sligo

- Slieve Blooms, Co. Laois

- Corravokeen, Co. Mayo, Extension Site

- Derry, Co. Mayo, Extension Site

- Kingarrow, Co. Donegal, Extension Site

Why is Bog Restoration Important?

Over the past 40 years, Ireland’s blanket boglands have undergone significant changes due to human activities. Afforestation, grazing, and other land uses have contributed to habitat degradation and these areas drying out. The primary aim of bog restoration projects is to restore and reverse the degradation of the blanket bog.

It is important that we conserve and encourage the rewilding of our native bogs to ensure that future generations can reap their significant benefits.

Blanket Bogs and Raised Bogs

Ireland is home to two main types of bogs: blanket bogs and raised bogs. While these bog types share many characteristics, they differ significantly in their distribution, formation, structure, and vegetation.

Blanket bogs are primarily found in the western half of the country and in mountainous regions further east, where annual rainfall exceeds 1,200 mm. Blanket bogs tend to cover larger areas, forming a continuous layer across flat or gently undulating landscapes.

Raised bogs are mostly located in the midlands, where rainfall is typically below 1,200 mm per year. They generally develop from lake basins and are often surrounded by agricultural grasslands.

Blanket bogs tend to cover larger areas, forming a continuous layer across flat or gently undulating landscapes.

Another notable difference between them is peat depth. Raised bogs have deeper peat layers, usually ranging from 4 to 8 metres, while blanket bogs have shallower peat, typically between 2 and 5 metres.

Blanket Bogs Flora and Fauna

Blanket bogs are essential for biodiversity, providing a habitat for a variety of plant and animal species that are specially adapted to thrive in the harsh, wet, and nutrient-poor conditions found there. This section highlights and illustrates several of the unique species found in Ireland’s blanket bogs.

Flora (Plant Life)

Fauna (Animal life)

Project Review

Ireland’s active blanket bogs are crucial to the survival of many spectacular native species of flora and fauna as they provide a habitat that is suitable for them to thrive in. Ireland’s peatlands are not only areas of natural beauty, they are also vital for the environment, as they store huge amounts of carbon.

Thanks to this bog restoration initiative and the dedicated members of environmental conservation teams across the country, our blanket bogs will be here for many generations to come.

Author:

Michael Malone

SOLAR ENERGY EDITOR

Michael Malone is Solar Energy Editor at Energy Efficiency Ireland. He is committed to highlighting the benefits of solar PV for people across the island of Ireland, and is eager to clear up some misconceptions which linger among the Irish public regarding solar energy.

Author:

Michael Malone

Solar Energy Editor

Michael Malone is Solar Energy Editor at Energy Efficiency Ireland. He is committed to highlighting the benefits of solar PV for people across the island of Ireland, and is eager to clear up some misconceptions which linger among the Irish public regarding solar energy.

Popular Content 🔥

The Importance of Blanket Bog Restoration in Ireland

Written by

Last edited

18/07/2025

With environmental issues becoming increasingly important, attempts are being made to return Irish bogs to their natural state, with conservation initiatives like the Active Blanket Bog Restoration Project. Preservation efforts such as this are among the most important environmental initiatives, as blanket bogs act as vital storage containers for large amounts of carbon.

The West of Ireland is home to some of the largest intact areas of active blanket bog in all of Europe. Blanket bogs are wild areas formed of peat soils, which formed over thousands of years partly from the decomposed remains of plants. ‘Active’ refers to a blanket bog that is still peat-forming or still growing. Among the last intact active bogs in Europe is Owenduff bog in Co. Mayo, part of the Wild Nephin National Park.

Efforts have been made to make more use of blanket bogs in the past. Forestry was seen as something that would boost the local economy in remote areas where blanket bog cover is extensive, and conifer species such as sitka spruce and lodgepole pine were planted in peatland areas. However in some cases, especially on very wet bogs, these efforts to establish commercial forestry failed as the trees did not grow well.

The bog restoration project is funded by the European Union and the semi-state forestry agency, Coillte. It is one of a number of successful projects and programmes aimed at enhancing biodiversity, in addition to policies designed to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels – such as incentives for solar panels in Ireland. There are 4 sites covering 1,212.3 ha in the bog restoration project consisting of unplanted, partially or wholly afforested blanket bog habitat.

Many project sites are located in north Co. Mayo, where the full range of blanket bog types occur from lowland to mountain blanket bog. Most of the bog here also lies within sensitive river catchments, i.e. where water quality is very high. This means that the protection of watercourses is an important consideration. The Active Blanket Bog Restoration Project aims to achieve the restoration of blanket bog at selected sites owned by Coillte.

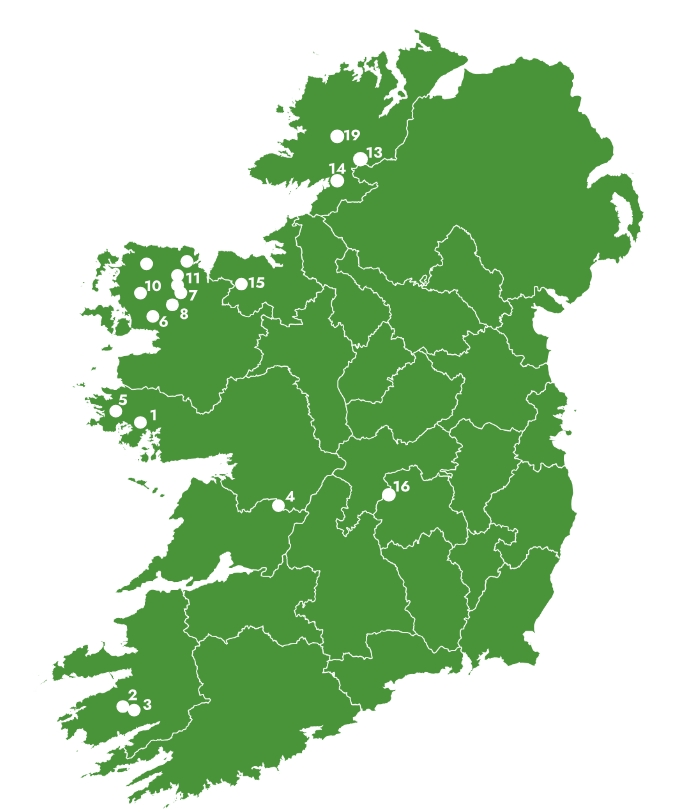

Restoration Locations

- Cappaghoosh, Co. Galway

- Garrane, MacGillycuddy’s Reeks, Co. Kerry

- Dromalonhurt, MacGillycuddy’s Reeks, Co. Kerry

- Pollagoona, Slieve Aughty, Co. Clare

- Emlaghdauroe, The Twelve Bens, Co. Galway

- Bellaveeny, Nephin Beg, Co. Mayo

- Eskeragh, Crossmolina, Co. Mayo

- Eskeragh, Crossmolina, Co. Mayo

- Owenirragh, Glenamoy, Co. Mayo

- Glencullin Lower, Bangor-Erris, Co. Mayo

- Shanvolahan, Crossmolina, Co. Mayo

- Shanvolahan, Crossmolina, Co. Mayo

- Croaghonagh North, Barnesmore Gap, Co. Donegal

- Carrick Barr, Lough Golagh, Co. Donegal

- Sessuegilroy, Ox Mountains, Co. Sligo

- Slieve Blooms, Co. Laois

- Corravokeen, Co. Mayo, Extension Site

- Derry, Co. Mayo, Extension Site

- Kingarrow, Co. Donegal, Extension Site

Why is Bog Restoration Important?

Over the past 40 years, Ireland’s blanket boglands have undergone significant changes due to human activities. Afforestation, grazing, and other land uses have contributed to habitat degradation and these areas drying out. The primary aim of bog restoration projects is to restore and reverse the degradation of the blanket bog.

It is important that we conserve and encourage the rewilding of our native bogs to ensure that future generations can reap their significant benefits.

Blanket Bogs and Raised Bogs

Ireland is home to two main types of bogs: blanket bogs and raised bogs. While these bog types share many characteristics, they differ significantly in their distribution, formation, structure, and vegetation.

Blanket bogs are primarily found in the western half of the country and in mountainous regions further east, where annual rainfall exceeds 1,200 mm. Blanket bogs tend to cover larger areas, forming a continuous layer across flat or gently undulating landscapes.

Raised bogs are mostly located in the midlands, where rainfall is typically below 1,200 mm per year. They generally develop from lake basins and are often surrounded by agricultural grasslands.

Blanket bogs tend to cover larger areas, forming a continuous layer across flat or gently undulating landscapes.

Another notable difference between them is peat depth. Raised bogs have deeper peat layers, usually ranging from 4 to 8 metres, while blanket bogs have shallower peat, typically between 2 and 5 metres.

Blanket Bogs Flora and Fauna

Blanket bogs are essential for biodiversity, providing a habitat for a variety of plant and animal species that are specially adapted to thrive in the harsh, wet, and nutrient-poor conditions found there. This section highlights and illustrates several of the unique species found in Ireland’s blanket bogs.

Flora (Plant Life)

Fauna (Animal life)

Project Review

Ireland’s active blanket bogs are crucial to the survival of many spectacular native species of flora and fauna as they provide a habitat that is suitable for them to thrive in. Ireland’s peatlands are not only areas of natural beauty, they are also vital for the environment, as they store huge amounts of carbon.

Thanks to this bog restoration initiative and the dedicated members of environmental conservation teams across the country, our blanket bogs will be here for many generations to come.

Author:

Michael Malone

SOLAR ENERGY EDITOR

Michael Malone is Solar Energy Editor at Energy Efficiency Ireland. He is committed to highlighting the benefits of solar PV for people across the island of Ireland, and is eager to clear up some misconceptions which linger among the Irish public regarding solar energy.

Author:

Michael Malone

Solar Energy Editor

Michael Malone is Solar Energy Editor at Energy Efficiency Ireland. He is committed to highlighting the benefits of solar PV for people across the island of Ireland, and is eager to clear up some misconceptions which linger among the Irish public regarding solar energy.